By J.J. Whelan

Frank was born and raised in Spam Valley, a private housing estate that sat like a sore thumb on the edge of the old mining village. It was where the incomers lived, folk who didn’t belong but fancied themselves a cut above the rest. They had bought houses there because they were considerably cheaper than any other place because of the location. The locals never trusted them, and the “Spam boys,” as they were known, didn’t help their case with their shiny Choppers, tidy haircuts, and stuck-up attitudes.

But Frank was different.

His old man was pure Gorbals, sharp, tough, and straight-talking. That fire ran in Frank’s blood. While the other Spam boys were polishing their trainers and pretending they were middle class, Frank was down the schemes, loitering outside the chippy with the local lads and sneaking into the youth club where the real life was happening. He never fitted in with the ones he was supposed to, and he didn’t care to. He liked it rougher round the edges.

At twelve, Frank discovered drink, cheap cider mostly, passed around in a field or behind the shops. He loved the feeling it gave him, the buzz, the boldness, the escape. He started robbing coins from his mum’s purse, just enough to go unnoticed and by the weekend, he had enough for a carry-out. A couple of bottles of El Dorado or a flagon of cider, and he was flying.

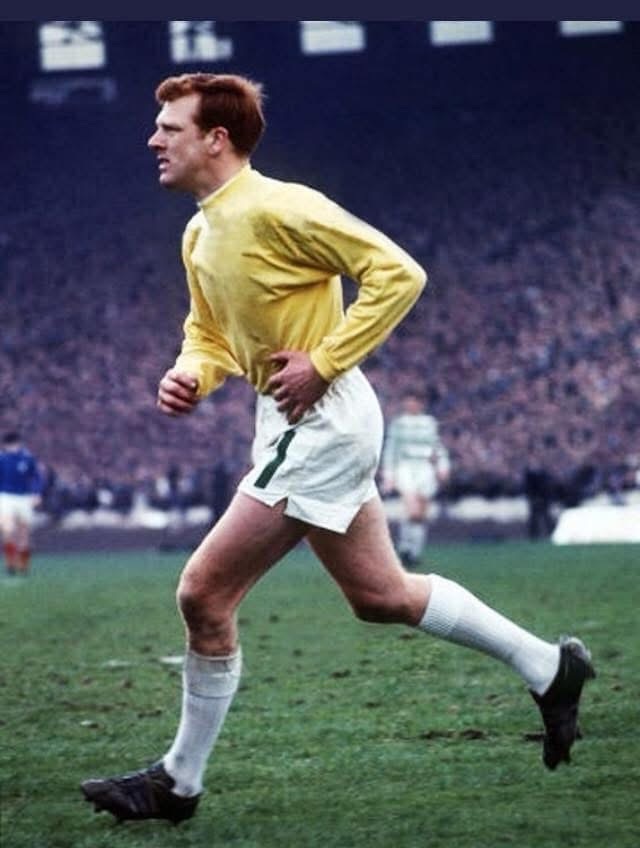

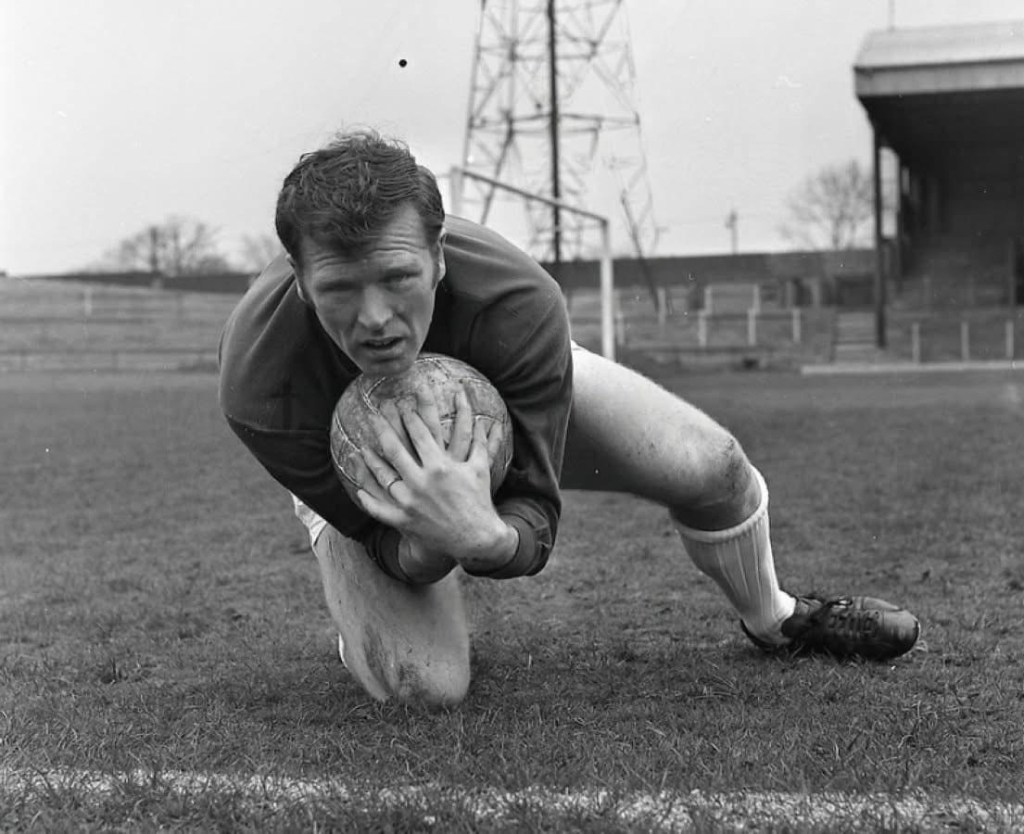

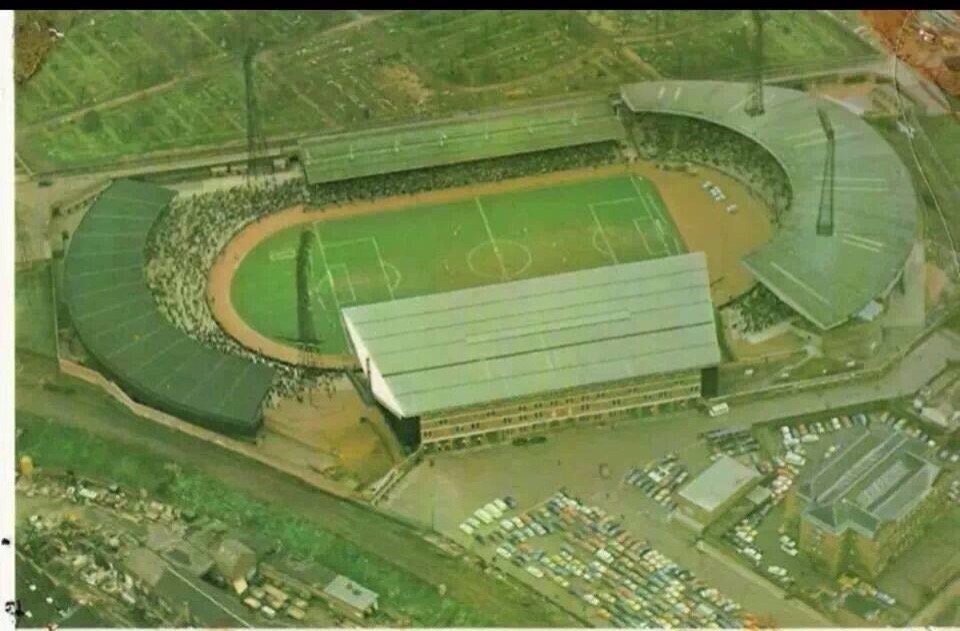

Football was his other obsession. Celtic, of course. His Da was a big Hoops man, and though he didn’t like the crowd Frank ran with, he loved that they shared the same team. So he gave Frank money for the games. While the other boys were scamming, stealing, or skimming to scrape together the fare to Parkhead, Frank had it handed to him on a plate, new scarf, money to get in and sometimes even a wee bit extra for chips and Irn Bru on the way home.

Frank was the only child of two working parents, his mum was a nurse and his Da foreman at the local factory so he never wanted for much. Spoiled, some would say. But his parents didn’t see it that way. They saw a happy, clever lad with a sparkle in his eye. Something they never had. They didn’t like the direction he was heading, the drink, the circles he was frequenting, the late nights but they thought it was just a phase.Let him find his own way, his Da would say. He’s a good boy deep down.

But the schemes had their own gravity. Frank, for all his privilege and posh postcode, was already drifting toward the pull of the excitement and the buzz created from all the chaos.

By the time Frank hit sixteen, the drink wasn’t enough.

He’d left school with nothing to show for it as he rebelled against the authorities. A couple of warnings, a record for fighting, and the respect from the lads who mattered to him. His parents still clung to hope. They thought he might settle, get a trade, find a good lady friend and be content. But Frank had other ideas. He was chasing the greater buzz, faster, harder, darker.

The schemes were his second home now. He’d bounce between flats like a stray dug on a trampoline, sleeping on couches, necking cider for breakfast, and dabbling in whatever was getting passed around. E’s at the weekend. Whizz through the week. A bit of prop when he had the money, which wasn’t often. He’d fallen in with older boys, the ones with connections, not gangsters, but lads who knew how to work the system: shoplifting, benefit fraud, selling fake gear, bouncing cheques and dodgy credit cards.

Frank had charm. He could talk the talk, and that Gorbals courage gave him edge. But behind the patter, he was slipping. His Da caught him once, bombed out his nut in the kitchen, and nearly flung him through the back door. His mum cried for days. They tried tough love, then soft love, then just silence. They didn’t know what else to do.

At eighteen, he was caught shoplifting with a blade in his pocket. Said it was for protection. The judge didn’t buy it, eighteen month suspended sentence. Frank treated it like a warning shot and kept going. The parties got darker, the nights longer. He was mixing vodka with Valium now, waking up in stairwells or not remembering how he got home. Total blackout material.

By nineteen, he was selling to feed his habit, not big-time, just bits of hash, maybe a few pills. But it was enough. In a stupid drunken fight the Police were called and he was lifted, caught in possession with intent. The court wasn’t lenient this time.

Nine months in Polmont.

Jail hit him like a Glasgow winter, sharp, brutal, and full of silence. The bravado didn’t count for much inside. You kept your head down, found your crew, and watched your back and arse. Frank learned quickly. He wasn’t the biggest, but he was smart and street wise, nobody pushed him far.

Letters came from his mum every week. His da didn’t write. Just one visit at the start, where he said, “you’re better than this son. Prove it“Then nothing.

Frank did his time, but the damage was done. He left Polmont at twenty, skinny, twitchy, and harder behind the eyes. The Spam Valley lad who once got money for Celtic games was now a jailbird, with a habit on his back and nowhere to call home.

Still, somewhere deep down buried under the chaos a voice kept whispering, “you’re better than this son. Prove it.”

Frank came out of Polmont thinking he’d seen it all.

But nothing prepared him for what came next the cold streets, the no-one-wants-you-here looks, the pals who’d moved on, and the ones still stuck in the same rinse-and-repeat cycle. He bounced back into the schemes like nothing had changed but everything had. His habit had him tight now. The drink came first, then the gear, then anything that numbed the ache of being alive.

He tried staying at his parents’ place, but that lasted two weeks. His mum begged. His da gave him one last speech, but when Frank nicked his mum’s engagement ring to sell for smack, the door closed for good.

The next few years were a blur.

Sofas. Hostels. Floors. Park benches. He burnt every bridge he had, robbed folk he called friends, sold stolen tools, made promises he never meant to keep. He tried to take his own life twice. The second time, he woke up in a hospital in the city, a priest at his bedside and a nurse with eyes full of pity.

That should have been the wake-up call. But it wasn’t.

His rock bottom came later, in the back stairwell of a tower block, shoeless, teeth smashed from a beating over a debt he couldn’t pay. He lay there for hours, half-conscious, soaked in his own blood, shit and piss, wishing he just wouldn’t wake up.

And yet… he did.

He staggered to the local rehab.

The Peter Wilson Centre not out of hope, but hunger. They fed him, gave him a warm blanket and a choice. Keep going as he was or try something different.

That was the start.

It wasn’t pretty. It wasn’t fast. It wasn’t some big Hollywood moment. It was meetings. Withdrawals. Raging headaches and rage at the world. It was shaking on the floor of a shared room. It was admitting, out loud, “My name’s Frank, and I’m an addict.”

He relapsed once, twice, actually. But he kept going back. One old guy at the meetings said, “Stick with the winners.” Frank didn’t know what he meant at first, but he figured it out. The lads who stayed clean? They weren’t saints. They just kept showing up.

After a year clean, Frank was a different man. Not perfect. Still skint. Still scarred. But steady.

He started working in the very rehab centre that helped him. Volunteered at first, making tea, mopping floors. Then a paid gig. His mum came to see him speak at a recovery night. First time they’d hugged in years.

His Da was slower to come round, pride’s a hard wall to climb over but one day, Frank turned up at Parkhead with two tickets for his Da and him. They stood side by side in the stands, scarfs around their necks, and said nothing. It was enough.

Frank still lived in the shadow of Spam Valley, but now he stood in the light.

Not because he escaped his past but because he owned it.

His Da’s words echoed within “you’re better than this son. Prove it.”